Art and War - by Christina Grant

Art and War

Since time immemorial art has been interwoven with war, whether depictions battles, armaments or propaganda.

From Ancient Greece ( Chigi Vase or Pitcher,

found in an Etruscan tomb c 640-50 BC); to

the famed Alexander mosaic found in Pompeii c

100 BC( depicting the battle between Alexander the Great and Darius III of

Persia); the Norman Bayeaux Tapestry (

which is actually embroidery) 1070; through to the Italian Renaissance and,

Ucellos - Battle of San Romano (1435 -50), Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of

weaponry ( multi barrelled cannon of 1481 or the Tank of 1487), or to Spains

Valazquez Surrender of Breda (1634-35).

Then their are the famous paintings of ships in the 19th century

by JMW Turner- the Battle of Trafalgar

1823/4 and his evocative Fighting Temeraire.

All these artworks had a common theme of

celebrating great victories and the armaments of war.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that art turned away from the celebration of war and began to turn to the loss and devastation on the ordinary people caught up in these wars. Not just the soldiers sent to certain death but also, the innocent children and women left in perceived safety.

We suddenly saw the end of glorification and

looked instead at the horror.

At the outset of WW1, the British Government did not support the idea of war artists, but just commissioned posters to recruit men to fight. However, when soldiers, who were also artists, returned from the trenches they exhibited paintings based on their own personal war experiences.

In May 1916, the first war artist, Muirhead Bone was appointed, soon to be followed by Nash and John Singer Sargent, (amongst others).

A Hall of remembrance was set up, which

subsequently became part of the Imperial War Museum.

‘Gassed ‘

by Sargent and ‘Menin Road’ by Nash became part of this collection.

Nash had been asked to paint a battlefield

scene. What he painted was a deserted, desolate, muddy landscape of tree stumps

and bomb craters.

Similarly, Sargent had painted a line of soldiers, blinded and injured being led to a field hospital.

Both these artists (and there were others too)

were still concentrating on depicting the war in a battlefield scenario.

But, within the next couple of decades, the

other side of the consequences of war, on the innocent and defenceless, were

depicted.

Today we will look at two of these artists, Picasso and Will Evans - one home grown and the other, internationally acclaimed.

Picasso painted his masterpiece Guernica in 1937, as an emotional response to the bombing of the Basque village. The German Luftwaffe were invited by Franco and his Nationalist Party to bomb Guernica in the Northern area of Spain. The village had no military significance.

The village was full of women and children as well as the elderly, as all the men who were able were absent fighting in the Spanish Civil War.

It is considered the most moving and powerful anti war painting in history, and is now housed in the Reina Sofia in Madrid, having been moved there in 1992.

Initially painted for the Paris exhibition in

1937, it travelled extensively throughout the world to raise money for the

Spanish Civil War relief. It was housed in the MOMA in New York for the

duration of the Second World War at the request of Picasso. He stated that he

would only allow it to be taken to Spain when the Spanish people had a free

democracy again.

Following the death of Franco and the

re-instatement of the monarchy and a democracy, the MOMA reluctantly

relinquished the painting.

Picasso himself stayed in Paris during WW2 and allegedly, when asked by a German ( referring to the Guernica painting) ‘ did you do it’ responded ’ No, you did ’!

This painting is oil on canvas and measures 25ft

6ins wide ( 776.6 cms) by 11ft 5 ins ( 349.3 cms) tall. It is painted in Black/

white and grey to mimic a photograph taken at the scene ( possibly influenced

by his photographer girlfriend Dora Maar).

It has a chaotic and distressing feel to the

tortured images of the people and animals depicted therein. Many theories

abound as to the symbolism used by Picasso in Guernica. The one I favour is

that the Bull is symbolic of the Spanish people, personified by Franco, and his

fascist aggression. Whilst the horse represents the female and the innocent,

faithful friend of man caught up in the horrific brutality of war.

The woman holding the dead child is

representative of Madrid mourning her quiet and innocent Spanish village in the

mountains.

On the day of the attack, most people were in

the marketplace set in the centre of the village. As the bombs dropped they

were trapped …unable to escape as the exit roads and bridges had been

destroyed. Hence, Picasso shows the scene in a closed room, with no escape,

implying oppression of innocent people and beasts.

Picasso drew on his Cubist and Surrealist

distortion of shapes and forms whilst painting this depiction of the horror and

devastation that war brings. His childlike drawings show the simplicity of form

and signs, evoking an emotional response to the victims pain and suffering. He

created a timeless image of terror and violence against man and beast

Will Evans ( 1888- 1957) was born in Waun Wen Swansea and was a noted artist who was also a respected art teacher and skilled lithographer. He later moved to Stanley Terrace in the Mount Pleasant area of Swansea.

Leaving school at 14, he became an apprentice

tin plate printer at South Wales Canister works, eventually becoming their

chief designer after attending lessons, part time from 1910 at Swansea School

of Art.

In 1937 he established the lithography

department at Swansea School of Art, at the request of the then principal,

William Grant Murray.(1877-1950) also, establishing the school of printing in

Rutland Street in February 1940, which had been planned for a decade.

Within a year it was destroyed by the German

Luftwaffe in the 3 nights blitz of Swansea in February 1941. (19th, 20th and

21st).

The attacks made a deep impression on the artist

- who had a birds eye view from his home in

Stanley Terrace (being one of the hills overlooking the town itself).

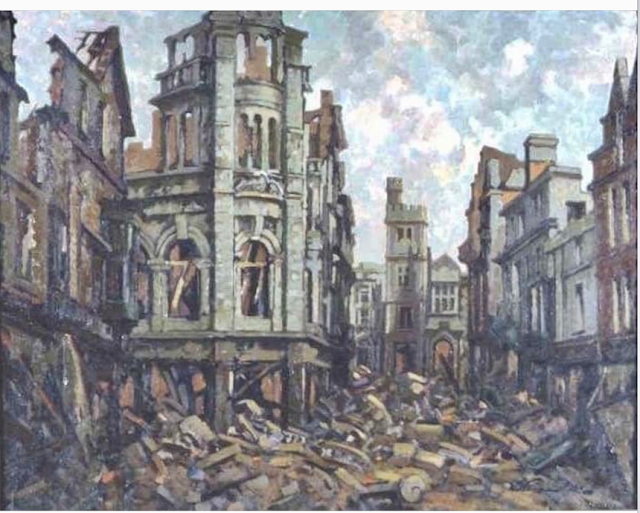

He documented the devastation in a series of

paintings which are of great historical importance and significance to the

people of Swansea, and 15 of these have been added to the permanent collection

of the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. It is a precious record, captured in paint, of

the aftermath and devastation caused by war.

His work is classical in style ( in complete

contrast to Guernica), and painted in colour. It shows the completely destroyed

Swansea Town centre, which was beyond repairing.( Indeed, on being rebuilt many

historical landmarks and streets totally disappeared, which is even felt to

this day).

St Mary’s Church ( the Civic Church of Swansea)

was so badly damaged that consideration was given to pulling it down but,

luckily, it wasn’t and was rebuilt in the 1950s. It is one of the few remaining

older building in the whole of the town centre and which stands on the site of

the original church built in 1328 by the Bishop of Brecon.

Following his death, Evans was given a memorial

show at the Glynn Vivian in Swansea in 1958, (just a dozen years after his one

man exhibition there).

As well as the artworks held at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, his works are also held at the National Museum of Wales and Swansea Museum (which is largely of landscapes of the Swansea area).

St Mary’s Square after the Blitz Glynn Vivian Art Gallery Swansea

Guernica : Gurnica translated by j. Dodman

Aldeasa 2001 isbn 84-8003-291-X

Museo National Centre de Arte Reina Sofia

Glynn Vivian Art Gallery:

Wesley Chapel 1941.

Entrance to Swansea Market 1941.

Castle Bailey Street Swansea

Castle Street from High Street

Ben Evans Drapery Store, view of the Castle

Street frontage

The Bank, Temple Street

Snow in Swansea

Castle Street Swansea

Castle Buildings 1941

Wrecked fish Shop

Bombed House and Shop

Mount Pleasant Church

The devastated Area, Swansea in 1942 (

watercolour on paper)

The Ruins of Ben Evans Store (watercolour on

paper)

Corporation Electricity and Post Buildings 1941

Imperial War Museum, London

Art UK

Presented as a talk

by Christina Grant to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery group : Contemporary

Conversations in 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment